Spring arrives in Midland at very different times each year.

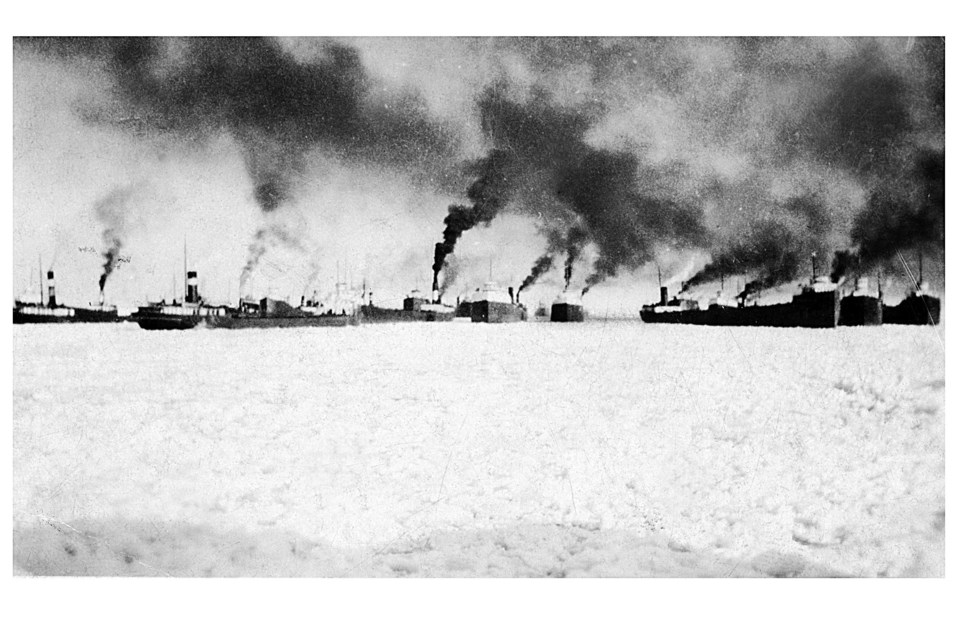

Early indications of spring had sometimes a dozen or more smaller canallers, small enough to pass through the narrow and shallow Great Lakes channels and canals. They wintered over in the inner bay.

As spring arrived, they steamed-up black smoke billowing from their stacks, covering the entire basin.

We took it as a fact of life - burning coal produced dirty black smoke. They needed steam to tune-up their foghorns. Now suddenly the blares lured older boys from school classes to the Inland Seas.

They were not present for roll call as the shore bosses were hiring onboard jobs. But it had been a warm pleasant winter in class.

The ice might not have completely gone from the inner harbour and on some nights skim ice would build, but not enough to worry the steel-hulled vessels.

Some days a strong west wind blew all the ice easterly to Waubaushene shores and crews worried, as the fishing smacks (sloops ready for fishing) were ready to get going.

Big dollars awaited the early catches that would be delivered to Yates Fishes House, recently located to the King Street waterfront. The then-shoreline was along the north side of present-day Bay Street in downtown Midland. Some 28 to 35 foot smacks were owned by Yates and one by an independent fisherman by the name of Cook. No first name appears, but it might have been Ike or Al.

The Cook name goes back to Midland’s earliest prominent citizens.

What sent me researching for this story started in mid-March on a Saturday morning was the sight from my waterfront view of Midland Harbour. I saw a wave-runner tearing up the harbour, turning circle after circle so he could attack the waves for his modest jumps.

For nearly a half-hour this circus went on. Did he not know that cold water kills? Did he not know that there was not any equipment or possible crews ready to rescue foolhearty operators?

On Saturday April 27th 1884, the first day the ice was out of Midland Harbour, Cook invited nine friends to join him on a sail to Pleasant Island, now present-day Present Island.

They enjoyed a good sail out but upon returning they experienced a sudden, westerly squall off Midland Point. They upset into the cold water and drifted south and easterly towards Flat Point, now called Paradise Point in Port McNicoll.

The chilling water started taking its toll. With no other vessels in sight, they drifted slowly for about two and a half hours, some standing on the downed mast and some sitting on the overturned hull.

They hollered and hoped for rescue.

On the Midland shore, some two miles westerly from where they floated, Richard Smith, captain of the government steamer Hilliard, stepped out of his father’s home on the hill at Dominion Avenue and Queen Street.

He thought he heard a distress call from the east, somewhere between Snake Island and Flat Point.

Smith rushed to the waterfront where he had a rowboat ready for the water. His brother George jumped into the boat with him and they rowed to the noise finding the floating vessel.

Two men named Hastings and Griffith were standing on the mast. Charles Hastings, a Midland jeweller and brother to the one standing, was already dead with his brother hanging on to him.

Smith decided quickly to remove these men.

“The hardest thing was leaving the other men begging to be rescued,” Smith would later recall, but he couldn’t safely overload his boat.

Arriving back in Midland, they carried the men to the beach and left them in care of his father and sister who had arrived wondering what was happening.

Another sailboat arrived on the scene, but because of the wind it couldn’t get close to the remaining men who had earlier boarded the now overturned fishing boat.

This second vessel, captained by a man named Davis, was travelling southerly from Pleasant Island and towing a rowboat.

Davis jumped into the rowboat, took off two men, Cann and Scarfe, and then headed to Midland.

Cann was the local telegraph operator and Scarfe a commercial traveller who had joined the party. Cann died before they got him to shore.

In the meantime Smith, returning from Midland, was joined by three other men: Switzer and John Clark and as well as Pease, a commercial traveller.

Young George Smith, a capable sailor, was transferred into the Davis sailboat to keep it nearby and safe.

When Richard Smith arrived back onshore with his second load, he found Griffith from his first trip, still on the beach. Griffith was frothing at the mouth, gasping for air. Upon closer inspection, Smith found that Griffith’s shirt collar had shrunk while in the water and was choking him. Smith cut it loose.

The shore rescue party had hot water, hot whisky and blankets ready, but it was some time before Griffith regained consciousness. Pease had died on the way to the town dock.

Three men dead, the rest nearly frozen and they knew truly, Cold Water Kills.

Three years later, Smith recorded that the survivors presented him with an engraved watch.

It read: “Presented to Richard Smith by those rescued in a boating accident on Georgian Bay 27th April 1884.”

No mention of Davis or young George Smith, the other rescuers, is found.

P.S. To the wave-runner. On the Sunday morning following your Saturday shenanigans, an easterly wind brought all the heavy ice from Waubaushene back to Midland Harbour.

Spring conditions are unpredictable.

Credit: Story of Early Midland and Her Pioneers, 1939 by George R. Osborne. Personal copy.

A copy may be found at Huronia Museum in Midland.