If we were alive 185 years ago, we would have found tensions rising in Ontario (then Upper Canada).

Embers of rebellion were being stoked and would, in a few short weeks, burst into flames.

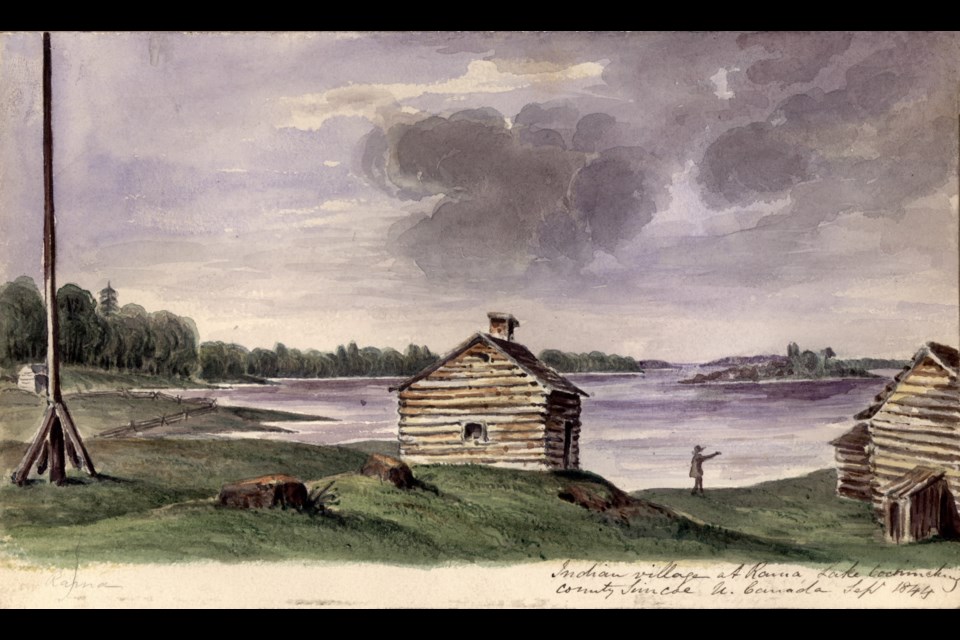

The story of William Lyon Mackenzie’s Upper Canada Rebellion is well known. Almost forgotten, however, was the role played by the Ojibwe First Nations of Rama.

Many white settlers of Upper Canada respected the First Nations. While those settlers who came from the United States (and there were many, perhaps as much as a quarter of the population) were raised on exaggerated stories of Indigenous savagery, British- or Canadian-born residents remembered the heroic role played by the First Nations in defending Canada during the War of 1812.

Indeed, Chief Yellowhead and dozens of Ojibwe warriors were, for example, present at the Battle of York in 1813, when the aging chief was severely wounded in the fighting.

Chief Yellowhead’s son, William Yellowhead, or Musquakie, was chief in 1837. When word of the rebellion reached them, the younger Yellowhead called a council, where he announced his intention to go to the aid of the government. Despite his people’s mistreatment over the years — uprooted several times and forced to give up their traditional lifestyle — he felt compelled to go to the aid of the British.

After winning over his people, he and his followers grabbed their weapons and raced for the scene of action.

By the time Chief Yellowhead and his men reached Toronto, the Battle of Montgomery’s Tavern (Dec. 7, 1837) had been fought and won, the rebel army shattered, and its leaders in hiding.

The atmosphere in the colony remained tense. Mackenzie was attempting to reunite the flames of rebellion from the safety of the United States, where he and his men enjoyed considerable popular support. At the same time, armed rebels remained at large, prowling the backroads and woods of Upper Canada, and many communities remained unsettled.

Among these villages in turmoil were Bradford, Holland Landing and Sharon, from which many of the most radical rebels had originated. Lt.-Gov. Francis Bond Head, worried this simmering resentment would once again boil over into violence, requested Chief Yellowhead and his band spend the winter encamped at Holland Landing to keep a watchful eye on events there. Should there be any unrest, they were to stamp it out immediately.

While the Ojibwe obliged, life in the hastily established camp was a miserable experience and they faced considerable hardships over the harsh months that followed. They were unable to do their winter hunting, so were reliant upon the government to tend to their needs. And yet, provisions were slow in coming, leaving the Ojibwe in dire straits. The combination of biting cold, hunger, and utter boredom made for a dreadful existence.

Come spring, Chief Yellowhead and his warriors returned home with the thanks of a grateful British government. They had done their duty and made a valuable contribution to maintaining the peace and security of Upper Canada.