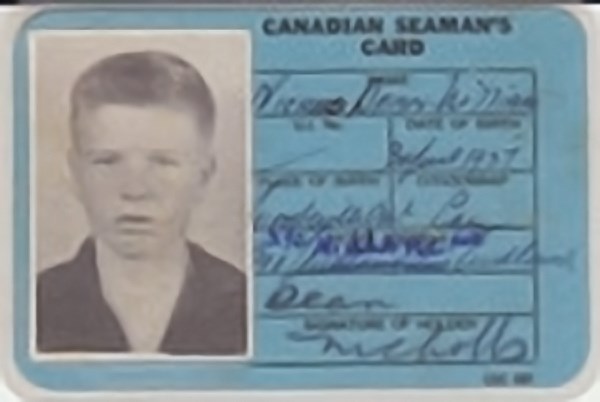

(Midland resident Dean Nicholls first came to the area in 1950 and was immediately taken with the size of Severn Sound and the ships being built in the area. While he later became a funeral home director, his younger days were spent crewing as a sailor on Georgian Bay. Today is the second installment of a three-part series that concludes Sunday.)

Into this story we now introduce Captain Malcolm Stalker, a cousin of the Burke brothers.

Stalker (1877 - 1969) had a somewhat noted career on the Great Lakes. From 1921 until 1926, he’s listed as captain on the Glenfinnan before spending the next three years on the SS Renir and then disappearing from any registry for some time.

We meet him again years later when he’s at the helm of the SS City of Dover operated by the Georgian Bay Tourist Company out of Midland.

In August 1952, at age 14, I signed on to the SS City of Dover as a coal passer.

The company, being short of coal and money, wanted the coal at the back of the bunker moved forward to the fireman who was “a fireman not a bloody coal passer,” thereby refusing to enter the bunker.

I couldn’t lift a shovel full but was able to get the shovel under the large chunks and drag them aft, in the lightless bunker, to the daylight of the engine room floor, beside the boiler.

After about three weeks, the company found some money, bought coal and I was laid off, unpaid. You had your meals and a warm bed that should have been enough, but if a hand was needed I would be first in line.

The wooden-hulled Dover was built in 1896 on Lake Erie’s shores at Port Dover as a fishing tug, measuring 74 feet in length and equipped with a single Scotch Boiler. She came to Honey Harbour in 1921 and was converted into a small freight and excursion ship.

Sold in 1949 to the GBT&SC, she came to Midland to serve the Georgian Bay Islands from Midland-Penetanguishene north to Cognashene, Go Home Bay and Parry Sound areas.

I became involved with the ship again in the spring of 1953 when I was approached by the Dover’s company manager and asked if I could paint. When I acknowledged I could, I was again hired ‘with guaranteed pay’ for after-school and weekend work to paint the ship so it’d be ready for the coming season.

Ahead of me was a memorable season of baffling problems: High water that required night watches, cooking duties, seldom pay and general turmoil.

Our new captain, Malcolm Stalker, connects us to the story of Captain Junis Macksey and the sinking of the Arlington.

Now a deckhand, I was introduced to our Captain Stalker as he arrived dockside appearing like any other local captain. Dressed with a shirt and tie, pressed pants, brightly polished, dark brown Dack’s Brogues, this to me was a captain’s uniform.

He stood about five-feet, six-inches tall, slightly overweight for his height, with the most cherubic face on any man I had ever seen. He looked as if he were continually puckered for a kiss or ready to whistle Yankee Doodle.

I soon was to learn that behind the face, things were different.

He climbed the steps to the second deck and on up to the wheelhouse by the ladder. From the traces of tobacco juice down the crevasses of his cheeks at the corners of his mouth, I could tell he was a chewer.

Shortly after we were away our mate Clancy Hilliard (Captain Stalker could never get his name right calling him Chauncey) ordered me to clean up passenger vomit on the steps from second deck to main.

I was on my hands and knees cleaning and holding my breath when I was grabbed by the back of the neck and stood up. The strong arm that pulled me to my feet was Captain Stalker, who said, “no deckhands are to be seen when I am using my side (port).”

“I am cleaning up which you just walked through, order by the mate”, I replied.

He looked at his shoes, walked over to the open hatch and barfed overboard, turned and said “now you have ruined my dinner.” He then started for the steps back up and said, “when the horn toots once, come up and get my shoes and clean them” and then up he went.

I had just cleaned up the mess when the whistle tooted a single blast. I went up and I could hear the captain raging that that damn deckhand had spoiled his dinner.

The wheelhouse was overcrowded with mate Hilliard, Captain Stalker and Captain Martin, who was a local knowledge guide, not a qualified captain, but served on the Dover for years as an honorary captain.

I squeezed in, got the shoes and departed. I thought about throwing them overboard while cleaning and drying them only to have the horn blow one short, again. Climbing the ladder and trying to squeeze into the house Captain Stalker asked where my pail and cleaning cloth were.

“Down with your shoes I’ve just finished cleaning,” I replied.

“Say sir,” he retorted.

“Yes sir,” I replied.

“Bring your pail, cloth and water,” he said, “be fast, we are soon into Cognashene and I want the windows clean.”

Away I raced and upon return I was led through the wheelhouse to the windward side of the ship. There was an ugly splat of tobacco juice down the portside window.

Our new captain spit into the wind, even I knew better than that. It blew back on him; even his shirt had splat on it.

Telling our chief engineer, Douglas Harpell as I got back to the main deck about my activities, Harpell replied “that’s why they call him Crazy Mac.”

Quizzing him, I asked where he got that information and was told, “if you sailed the lakes you would have heard about him.”

In the weeks that followed, Captain Mac first took a dislike to and fired our beloved elderly cook. She was working to keep ahead since her husband was a disabled sailor without pension or medical assistance (much common in those days).

Chauncey then suggested that his wife was a steamboat cook and if he and his wife could have the berth behind the pilothouse, she could finish the season for us.

Arriving back home our manager liked the idea right away, but Stalker dragged his feet. The rest of our crew assumed that the captain was getting ready to shove our first mate off next.

Captain Stalker resented Clancy Hilliard, parading around dressed like an officer with a braided cap and decorated epaulets often mistakenly called ‘captain’ by passengers.

Anyway, the deal went through, Mrs. Hilliard arrived and we were a full crew.