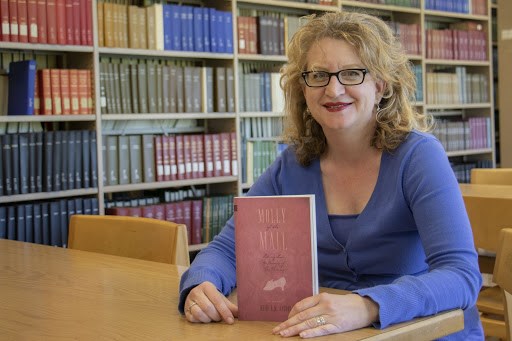

Despite the pandemic, the board of the Stephen Leacock Associates carried on its tradition of bestowing the coveted Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour when they announced that Heidi L. M. Jacobs won the 2020 medal for her novel Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass and Purveyor of Fine Footwear, published by NeWest Press.

The award of the medal is accompanied by a prize of $15,000.

The two runners-up, Amy Spurway (for her novel CROW, published by Goose Lane Editions) and Drew Hayden Taylor (for his play Cottagers and Indians, published by Talonbooks), will each receive a prize of $3,000.

Due to the pandemic, there was not Gala Dinner this year. Instead, the authors' achievements will be celebrated instead next year.

The winner and one of the runners-up have each written an essay about the experience. To reach Spurway's essay, published yesterday, click here. Today, is Jacobs' essay.

********************

When I was small, my mum had a stylish canvas tote bag. It was square, smoky sage in colour, with brushed silver handles. It was covered in words in Herculanum font in that vague colour that sometimes gets called taupe.

I remember sitting on my parents’ bed, waiting for my mum to get ready for our afternoon of errands and this tote bag was sitting beside me.

I had just started to read and I read everything I could find to practice. I read the words on her tote bag aloud: “London Paris Milan Tokyo. London Paris Milan Tokyo. London Paris Milan Tokyo.”

I knew they were all cities. I let the words wash over me as I read them over and over. As my mum sat down beside me to slide on her last shoe, I asked “Why isn’t Edmonton on this bag?” I recall that she repressed a smile and retied a ribbon on my ponytail that probably didn’t need retying.

“Well. We’re a little different,” she said.

As we got into the car and drove away to start our errands, I was convinced there was an error on the tote bag.

Since winning the 2020 Stephen Leacock Award for Humour, I’ve been asked many times about the origins of Molly of the Mall: Literary Lass and Purveyor of Fine Footwear. The more I think about it, the more I am convinced my novel is a long-overdue response to that tote bag.

In the early chapters of my book, Molly writes a letter to Jane Austen asking for advice on how to become a novelist: “I recall you advising your niece Anna. . . that ‘three or four families in a Country Village is the very thing to work on.’”

Explaining how she lives in Edmonton not a country village and sells “low-to-mid quality” footwear in a Very Large Mall, Molly queries: “Without three or four families in a country village, will I ever be able to write fiction?” Much of Molly of the Mall is a meditation on Edmonton as a possible setting for fiction.

Edmonton, for Molly, is a creative enigma. On the one hand, she assumes Edmonton is not worthy of literary depiction because she never sees anything like it in the literature she reads. Yet, on the other hand, she wonders why no one has “waxed poetic about the cold winds that shake our darling buds of May.”

In order to remedy Edmonton’s literary invisibility, Molly tries to take existing literary models and impose them on Edmonton and the prairies. She turns Burns’s “Ye Banks and Braes o Bonnie Doon” into an homage to Bonnie Doon, the jarringly misnamed neighbourhood of Edmonton.

Her attempt to write an “historically accurate, gothic bodice-ripper” set in Saskatchewan, “the most gothic of all the prairie provinces,” fails to develop beyond a preliminary plot chart.

In the course of the novel, Molly starts to talk back to the literary tradition when the literature she reads doesn’t mesh with her experience.

After reading the first few lines of Frost at Midnight, on a bleak Edmonton winter day, she offers this retort to Coleridge: “You want to talk about frost, Coleridge? Do you? Well, let me tell you about frost. Walk a mile in my seasonally inappropriate footwear in twenty-below-zero, and then we can talk about frost.”

Slowly, Molly realizes, it’s not the limitation of Edmonton as a site of literature but the limitation of the definition of Literature she has inherited.

I don’t want to say too much about the end of the novel, except to say that Edmonton is more than a setting in this book. Edmonton is a character that evolves in Molly’s mind as she navigates her own creative life and finds her voice.

Molly’s quest to make Edmonton into a setting worthy of literary fiction loosely mirrors my own struggles to write fiction in and about Edmonton. For me and many of my friends, Edmonton seemed to be a place we felt we needed to leave in order to have any sort of creative life.

When I left Edmonton to do a PhD in the U.S., I hoped that circumstances would one day bring me back to live and work there. That has not happened: life and jobs have taken me elsewhere.

Edmonton, however — with its stunning river valley, its massive blue skies, its warm cafés, its bustling university, its endlessly long summer nights, and its crushingly short winter days — was where my mind first wandered when I started writing fiction and where it still roams in search of stories.

--

The financial contributions from sponsors and donors are essential for the Leacock Associates to award the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour each year. Without donations, the award will die. If you are keenly supportive of Canadian literature, then please help to ensure that the medal continues to be awarded for many years in the future. To make a donation you can click here.