From self-isolation in his Kempenfelt Bay-area home, George Taylor watched the annual transformation last weekend as its icy surface changed back into liquid water.

The early indications, say observers, are when the weather gets warmer and the ice becomes a darker green and then it turns soft and slushy. Often, it takes a wind to blow through to push the already vulnerable ice out to oblivion.

“There is a sound to the movement. The big chunks have a grinding sound whereas the smoothie stage sounds just like a glass crushed ice,” said Taylor, a retired lawyer and former Barrie-area MPP from 1977 to 1985.

Keeping an eye on ice out has been a fascination for many over the years, some of whom recorded exactly when the bay or the lake froze and when it melted.

Among them was by Dr. William (Bill) MacDonald, who put together a paper he called The Ice History of Kempenfelt Bay, 1852-2002, capturing the many collections, which now resides with the Simcoe County Archives.

Farther up the lake in Orillia, Bob Bowles keeps an eye out on both Lake Simcoe and Lake Couchiching.

As a retired Ontario Hydro engineer and naturalist, Bowles wondered how the changing climate might impact when and how the lakes would freeze up and then thaw. So, 25 years ago, he began recording the annual processes.

“I wanted to get an idea of how the world was changing,” he said.

But ultimately, he discovered, the lakes haven’t been washing up any clues. He was able to discern no obvious patterns.

Another was Bob Sarjeant whose home in Shanty Bay proved the perfect perch from which to watch the evolution of Kempenfelt Bay, starting about the middle of the 20th century. His legacy continues through local biologist Alex Mills, a York University professor who now has those records and tracks the coming and going of the ice in Barrie.

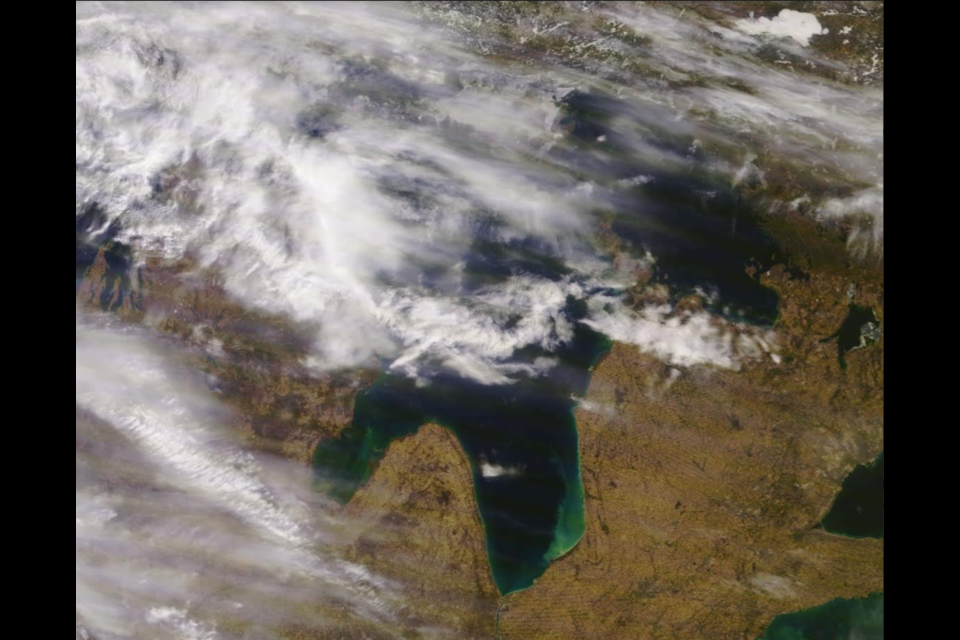

While there are now more scientific methods, including the use of satellite images, the human observations are rich for the 170-year story they tell, says Mills, who believes those records could be among the oldest of a lake’s freezing history.

While the recent history of the lake may not, on its own, demonstrate a pattern, Mills says the longer history shows the ice season has shrunk by about three weeks since those early years when those observations were first recorded.

“There’s been more change in the freeze-up date than in the thaw date,” he told BarrieToday, pointing to a two-week shift in freezing and then a one-week shift in ice out.

All that information gathered from many generations of those who lived along the shores of Kempenfelt Bay and Lake Simcoe are now getting wider attention, Mills added.

“It is of interest as a signal of climate change,” he said. “This data set is now part of an international data set… of dozens of lakes with over 50 years of history.”

The new data set is drawing from records of lakes the world over for which there are records exceeding 50 years, including the records from Barrie.

And although the ice might be gone, Taylor’s eyes still turn to the bay. Last Thursday, just four days after its surface turned back to water, Taylor spotted the first sail boat on the lake, followed by a jet ski.

Summer must be near.